History of Dwell

Listen to Dennis and Gary share more about Dwell's history in these Dwell on These Things podcast episodes:

In 1970, some Ohio State University students, including our church's founding pastor Dennis McCallum, began printing an underground newspaper in the basement of their rooming house, a popular practice in those days. They called their paper "The Fish." They derived its name from the Greek word for "fish," ichthus, which was also an acronym used by early Christians meaning "Jesus Christ, God's Son, the Savior."

The paper contained articles on current events, cinema, music, and philosophical issues. The group passed out free papers on North High Street next to the Ohio State University, and engaged in dialog with other students.

The paper contained articles on current events, cinema, music, and philosophical issues. The group passed out free papers on North High Street next to the Ohio State University, and engaged in dialog with other students.

Their rooming house on East Lane Avenue came to be called the “Fish House,” because they printed the paper there. That year, they started a weekly Bible study and discussion with free dinner. The paper ran a regular ad inviting people. People called these meetings the “Fish House Fellowship,” and the name remained for the next 12 years — long after the Fish House was gone.

Co-founding pastor Gary DeLashmutt moved into the house in 1971.

FOUNDATIONS

For years, the fellowship was a disorganized association of house-based groups scattered around the Ohio State campus and the city’s North Side. The leading figures started dozens of home Bible studies, most of which fizzled after a year or two, but not before seeing many people come to faith. Additional groups were planted by Dennis’ mother, Martha, who was a gifted leader. Leaders set direction through advice and personal influence rather than through leadership offices. By 1974, a dozen groups survived, comprising around 200 people.

During this period, the group’s theology was influenced most by four strangely contradictory sources: Francis Schaeffer and Oz Guinness of L’Abri; Plymouth Brethren teaching typified by Miles Stanford; grace-oriented Bible commentary like that of William R. Newell; and Chinese church-planter Watchman Nee. Ray Stedman’s book, Body Life, was also influential. Yet such eclectic approaches were common during the Jesus Revolution in full swing during those years.

The theological emphases they gleaned from these authors were:

- The centrality of the grace of God, and a critique of legalism

- The importance of reaching out to non-Christians with the gospel

- The importance of learning Christian truth, including the Bible, theology, church history and contemporary social criticism

- The importance of staying in touch with contemporary culture, with a pointed rejection of anticultural fundamentalism

- The importance of developing Christian community, including a network of deep relationships

- Personal discipleship, which was practiced as early as 1971. Reading Robert Coleman’s The Masterplan of Evangelism led Dennis and other leaders to seek out those they could disciple. Early on, only a handful of members were discipled, but the practice spread to where most people in a group experienced it. That feature is still dominant today

- Duplication or multiplication of groups

Dennis, Gary and others often attended Bible studies taught by former Campus Crusade staffers Gordon Walker and Ray Nethery. These men were instrumental in the early equipping of leaders, and Fish House enjoyed an informal alliance with another group in town founded by these men. But in 1974, when Walker and Nethery joined a larger group and moved in a different direction theologically, Fish leaders broke with them and their group. Nethery later also broke with the group.

Based on teaching and reading circulating in this group, Fish leaders began to envision a return to primitive Christianity as seen in the New Testament. Dennis and Gary studied church history at Ohio State and on their own, eventually reaching the conclusion that church tradition and practice held no value when it came to mapping direction for God’s people. They made a concerted effort to erase the blackboard and reevaluate how to design wineskins in light of the New Testament pattern, modified for modern culture.

Specifically, they rejected the clergy-laity concept in favor of “every member ministry.” Members were urged to find ways to serve in accordance with their gifting. The group increasingly came to view being a do-nothing as a serious failing.

The group shared a dread of shallowness, outward “churchy” piety and formalism. They saw the importance of keeping the church outwardly focused, and sought to avoid what they perceived as a tendency in the American church to be inward and out of touch with contemporary culture.

CALIFORNIA

In 1974, several leaders, including Dennis and Gary, decided to seek formal graduate study. They went to Los Angeles where they studied for two years at Christian Associates Seminary, which promoted itself as a place to train leaders of “street-oriented” ministries. Most faculty had been Campus Crusade staffers earlier in their careers. The Fish students found themselves often at odds with the interpretive line taken at the school, but on the whole it was a good educational experience. The school’s inability to grant accredited master’s degrees came back to haunt Fish leaders.

RECONSTRUCTION

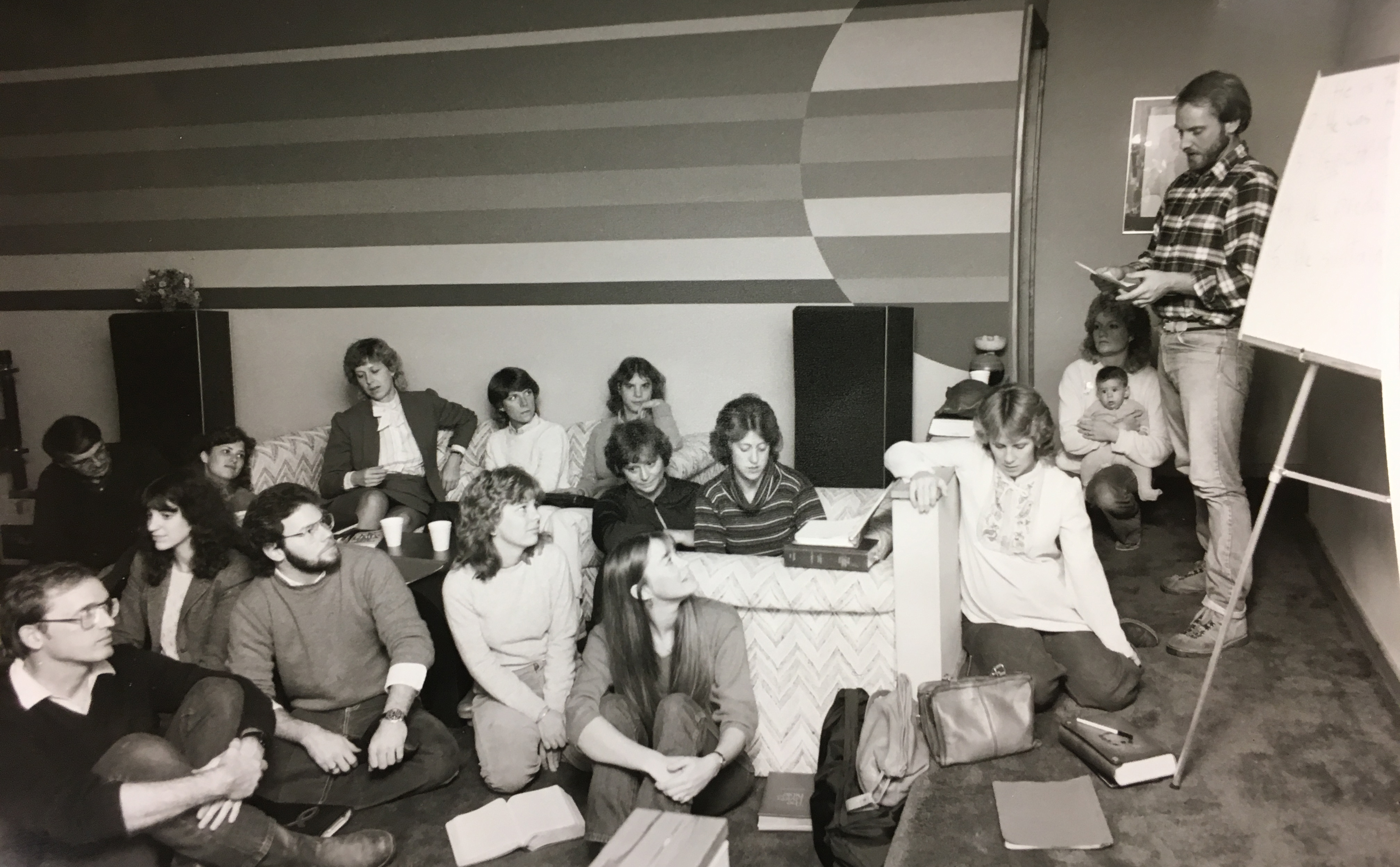

Upon returning to Columbus in 1976, those from California rejoined leaders who had remained behind to oversee the now smaller group of about 60 students. They had concluded from their studies that a local church should be led by a board of elders, so they elected five or six elders and set about starting new home Bible studies originally called “small groups.” Their purpose was fellowship, and members were all believers. Membership was by invitation only.

Alongside the small groups, Dennis and Gary had concluded that the early church often operated larger public teachings. For example, Jerusalem converts met together in homes and at Solomon’s portico (Acts 2:42-47). Paul taught in Ephesus at a lecture hall and also from “house to house” (Acts 20:20). At centralized teachings, clusters of home groups could share a teaching and gain access to better trained preachers. Today, members refer to these meetings as Central Teachings (CTs).

Fish also planted a third type of group called “bush groups.” These were outreach groups intended to engage new neighborhoods or affinity groups. Typically, newer believers would ask to have one where they could reach friends and family. The term comes from the idea of getting out into the African bush — in other words, away from established groups. As home churches later enjoyed success in outreach, bush groups diminished. But, even today, several are typically launched each year. Successful bush groups might be redefined as home churches. Otherwise, they usually don’t last more than a few months.

Very quickly, people were attracted to the new Bible studies. By 1980, the group had grown to more than 500. During this entire period, all leadership participated on a volunteer basis. Dennis and Gary made their living by starting a painting company. Not until 1980 did the group open a bank account so they could acquire space for meetings. They leased 9,000 square feet in an office-warehouse.

The venue was literally underground, in the basement suite of a larger building. Leadership had track lighting put in throughout the space to replace fluorescent lighting already there. One third of the space equipped with spool tables and chairs was the smoking section, although people continued to smoke in the rows of seats, and had to be admonished to move.

Not until 1981 did the group hire paid staff. Dennis and Gary were placed on part-time salary and began working to turn their business over to employees. By now the church had grown to nearly 800 members. During this first decade, when no leaders in the church received pay, members developed deep convictions about lay ministry. To this day, members shoulder the bulk of ministry and undertake extensive training. The group’s “every member ministry” ethos grew deeply during this period.

When it became evident that the Fish House Fellowship was becoming a large church, the leadership decided to incorporate as a church under Ohio law. The group was still going by its original name, although by this time, it was nonsensical. They had been publishing a magazine called Xenos, and that played a role in the renaming. The 80 or more leaders were given three choices, and voted to call the new corporation Xenos Christian Fellowship. The name is derived from the Greek word xenos, which in the New Testament denotes "sojourners in a foreign land," a biblical description of Christians whose ultimate home is in heaven (Hebrews 11:13).

From the beginning, Dwell has focused on reaching not only unchurched people, but anti-church people — those determined to stay away from more traditional churches. This is why Dwell meetings don’t follow the pattern most expect. One of the most notable features is the absence of worship services. Our leaders have a different understanding of worship.

RAPID GROWTH

During a period of rapid growth from 1980 to 1984, Dwell leaders converted their network of small groups into home churches. Home churches were larger, often 50 or more members. Their mission was not only fellowship, but also outreach, discipleship and multiplication. Each home church set out to win new members, train new leaders, and finally partition into two home churches. The intended result is a self-replicating movement. The strategy has born extensive fruit and is still our main means of growth.

As home churches multiplied and spread throughout the city, they became increasingly successful at reaching not only students, but also people in their 30s, 40s and 50s. Dwell had to shoulder the increased burden of creating a quality children’s ministry.

EQUIPPING

Beginning in the 1980s, the church developed a fairly elaborate system of coursework intended to raise up qualified new home church leaders. Courses generally charge tuition, include assigned homework and have graded tests. These courses are required for those seeking to become HC leaders.

By 1984, the average home church attendance reached 2,050. Concurrently, the number of lay leaders rose from 50 in 1980 to more than 200 in 1984. The two original CTs grew accordingly. Dwell added a third in 1986 and a fourth in 1988. In accordance with the concept of multiplication, the group prefers to plant new CTs with new teachers, rather than focus on a single, well-known teacher. To accommodate new meetings, Dwell acquired more space, including an elementary school with a multipurpose room and a larger leased warehouse-office suite most people called “the Warehouse.”

REPUTATION PROBLEMS

Through the years, Dwell has aroused suspicion and hostility for a number of reasons. Some area churches, especially theologically liberal churches, resented losing many members to Dwell. The emphasis on lay and student leadership grated against many churches’ views. Conservative churches deplored the smoking, beer drinking and profanity often seen and heard at Dwell meetings.

In 1984, The Columbus Dispatch ran a full two-page spread on Dwell, citing hostile priests and pastors denouncing the group. Other voices joined in, including a group known as the Cult Awareness Network. Dwell elders got feedback from the network and from area pastors before launching an internal inventory that uncovered a number of incidents involving cult-like behavior.

In response, the leadership launched numerous reforms. Training was dramatically increased. The elders reasoned that leaders lacking knowledge might rely on pressure instead of persuasion. That could lead to some of the bossiness evident in some groups. The elders also went back over all their training materials to root out statements that could be misinterpreted as condoning the controlling of members. They also convened several re-evaluation meetings with existing leaders to rethink their philosophy of ministry, including the possible overuse of church discipline.

A DIFFERENT DECADE

By 1991, Dwell (then known as Xenos) had grown to more than 3,500 people. Because of the hundreds of children now involved, the Warehouse no longer could meet the group’s needs. Staff undertook a long search to lease property to accommodate parking needs and city restrictions on assembly-rated buildings. Nothing suitable could be found.

They were under pressure to expand the elementary school, and they needed office space. The lack of space caused church growth to shudder to a halt. People were turned away from teaching venues because there was no remaining space for kids. Under these pressures, the elders brought to the leaders a motion to build a facility to house the increasingly expansive ministry. After a few weeks of debate, the 400-person combined leadership team voted 90 percent in favor. The elders began another search, this time for a building site.

Some people in Dwell expressed suspicion about the decision to build. The plan conflicted with earlier arguments that church buildings were wasteful, and not in step with the New Testament primitive church. Efforts to introduce more organization also created growing suspicion that Dwell might be abandoning its earlier vision.

As the church searched for a suitable site that would not limit future growth, the membership had to face several grave issues, including our longtime tradition of weak financial giving. Although Xenos members had a strong ethic of self-sacrifice in other areas, giving had never been strong. Leaders had never passed the plate at meetings, referring, instead, to a box in the rear where people could leave donations if they wanted. Our annual budget was barely over $1 million with attendance of 3,500.! It was clear that giving would have to increase.

Leaders began taking collections and organized a pledge system to cover the costs of a new building. They raised $3.5 million in pledges, and assumed they could borrow the rest of the cost of a suitable building. That turned out to be wrong.

DIVISION

During the early ’90s, Dwell underwent internal upheaval, eventually resulting in our first large-scale division. The causes for the division were complicated, involving some interpersonal conflict but also important substantive issues.

Many members came to distrust some of the elders, who were taking the church in new directions but were unable to reach some of their goals, such as constructing the new facility. Although they were eventually able to buy a premium site located near a freeway exit, unexpected legal and zoning blockages continually stalled the beginning of construction. Also, a savings-and-loan crisis broke onto the credit scene in America, making it nearly impossible to borrow money. Elders announced the group would have to wait to build, perhaps for years. In fact, they purchased the site in 1991, but didn’t open doors at a meeting facility until 1997.

Some members interpreted this failure and the lack of growth as a sign that God’s power had departed from the leadership of the church. They believed the elders were operating in the energy of the flesh. The introduction of new features like pledges and collections were also seen by some as a sellout of the original vision.

In addition to these problems, the leadership of the church was divided over issues of doctrine and practice. A group of home church leaders and counselors in the church were increasingly involved in: victim advocacy, including recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse and ritual sexual abuse; multiple personality disorder; and an emphasis on the emotional lives of Christians, against what was pejoratively called a “functional approach” to Christian living. Dwell elders were generally against all of these new views.

Some leaders were advancing an approach to Christian leadership that the elders felt was soft and excluded high commitment. Elders were hearing a growing chorus from members who felt marginalized by the church’s ethos, which increasingly resulted in discontent and suspicion. The central question seemed to be whether to view the church primarily as a place of healing or as a base for advancing into Satan’s territory.

During a colloquium scheduled by the elders with the counseling department, the different sides wrote papers and debated their views. The counseling department included the thought leaders for the opposition. A meeting of the entire church followed, where leaders and elders presented areas of agreement and disagreement. None of these measures resolved the growing conflict over the church’s future vision and ethos.

This dispute also correlated with the rise of the so-called “Toronto Blessing.” Some Dwell members were caught up in nearby conferences and urged other members to join in. Elders decided this revival reflected extremist views and practices that had no place in the church. They went on record publicly with their criticisms, to the dismay of many members who considered it divisive. Over 300 members left over this episode.

As dissent reached a crescendo in 1993, many called for Dennis to resign. The charges against him were subjective: He wasn’t caring or sensitive enough, or he cared more about mission than people. He was never charged with any objective wrongdoing like theft or sexual misbehavior.

The elders met to discuss whether their direction was somehow wrong or whether the problem was more the result of a generalized negative attitude toward human leadership. Dennis maintained that there was nothing wrong with himself or the other elders, and that they should stand their ground.

Finally, the elders decided to have it out with the dissident group in the church. At a meeting of all church leaders and staff (about 500 people), elders announced there would be a debate on the suitability of the current elders to lead the church. They urged everyone to bring their suspicions and complaints out in public, and after three hours of debate, the group would vote on whether to keep or remove each existing elder.

Instead, the debate began at 9 a.m. and lasted until 5 p.m. without a break. After heated exchanges, complete with accusations and counter accusations, leaders voted by secret ballot. All existing elders were retained by margins of not less than 85 percent. Two-thirds majority had been required to pass. Dennis got the fewest votes, but he reported being happy after the meeting that now the church could move on.

After the referendum, Dwell elders authorized Dennis to set in writing his vision for the church. After revisions by other elders, they presented the paper to a meeting of the combined leadership and called for a vote of affirmation. The paper established a Servant Team with new restrictions and expectations for leaders. The paper was affirmed by 85 percent of the 350 leaders and staff, much to the dismay of a vocal minority.

People began to leave. During 1993 and early 1994, more than 1,400 people left the church. The church, now down to about 2,000 in attendance, went through a period of recovery as members sought to reacquire our earlier focus as a multiplying home church movement. Within two years, the church again began to grow, eventually reaching more than 6,000 in average attendance. The changes in the Servant Team have proven to be a great success, with several hundred on the team today. The changes also brought an end to the problem of weak financial giving, and today Dwell has become a generous church.

STUDENT REVIVAL

Beginning in 1997, the church experienced a remarkable awakening among students at Ohio State and Columbus State Community College. Xenos’ college ministry was languishing and hadn’t grown in years. But as the group bought into the vision of a multiplying home church network, students started coming to faith in growing numbers. Simultaneously, the college group took over leadership of Dwell’s high school ministry.

Over the next 20 years, the college group grew from three house churches to more than 60. High school house churches grew from four or five to more than 40. To this day, Dwell is dedicated to bringing the relevance of God’s message of grace and purpose to a continually changing young culture.

ADVANCES IN MISSIONS

Dwell has maintained a strong burden for international missions. In the 1980’s Dwell developed a strategy that, in the end, yielded limited results. The strategy was later reformed, and since then Dwell has made huge strides in missions.

One of the main changes was a shift from exclusively sending North Americans to also seeking to equip and fund indigenous church planters and evangelists. The church has supported hundreds of Indigenous workers in multiple unreached fields. Dwell has set aside millions of dollars of its yearly budget for missions. Indigenous workers supported by the church have planted thousands of local churches and won tens of thousands of new believers into fellowship.

CHANGING OF THE GUARD

In 2019, Dennis and Gary, along with several other elders, stepped down to make way for new, younger leaders. Conrad Hilario and Ryan Lowery took over as co-lead pastors. Both Dennis and Gary continue to serve in part-time roles and lead their own home churches.

Among other changes, the new leaders decided it was time for a major change–a new name. Why did Xenos change its name to Dwell? Part of the reason was practical–”Xenos” is hard to pronounce and unfamiliar–and part of the reason was to better describe us–a place to dwell with the Lord and in community with other Christians.